Lawrence County

Historical Society Journals

Index

Fall 1978

Vol. 1 #4

Black Rock Pearling and Button-Cutting

Industry

Glynda Stewart, Powhatan, Arkansas

Lawrence County

Historical Society Journals

Index

Fall 1978

Vol. 1 #4

Black Rock Pearling and Button-Cutting

Industry

Glynda Stewart, Powhatan, Arkansas

,

Pearling and button-cutting go together like ham and eggs, for in reality, there probably would not have been a button-cutting industry in Black Rock, county of Lawrence, had Dr. J. H. Myers not become interested in pearling. The 1904 Stockard history describes Dr. Myers as a "scientist, naturalist, and business man." It goes on to say that Dr. Myers "having read of valuable pearls being found in clams or fresh water mollusks, began investigating the matter in Black River some two miles above the town of Black.Rock. He had only opened a few hundred muckets when a ball pearl weighing 14 grains, fine luster, and pinkish color was found. This was sufficient to start the work right."This same history credits Dr. Myers with finding the first pearl and with being the first promoter of the button industry in Black Rock. Walter E. McLeod in his history book "The Centennial Memorial History of Lawrence County" published in 1936 says that Dr. Myers "may be said to have been the father of the pearling industry on Black and White Rivers."

During the years 1897, '98, and '99 many people began "hunting for pearls." The number steadily increased each summer until cold weather and high water shut down this infant industry. Hundreds of these people "grappled" for muckets by hand putting them in sacks, much like one would in picking cotton.

Dr. Myers is quoted as saying, "In 1898, the find was much larger,also the number of hunters. I have seen as many as five hundred men, women and children of all sizes and colors on one bar, indiscriminately mingled, wading in as far as they could reach bottom, some opening, others gathering shells. The wealthiest bankers, lawyers, merchants, doctors, etc. , their wives and children wading in with the poorest (people), all laughing and singing, working day after day the summer through."

My dad, Samp Hill, recalls as a youngster in the early 1900's, his dad would take them digging or grappling for shells just for the pearls after they had laid their crops by. While talking to him about the pearling and button industry he told me about him and mother taking me grappling for shells when I was a small child. I can remember going to the river and being placed in shallow water on a sand bar with my parents close by, but instead of remembering digging shells, I only remember being tumbled over in my very shallow water the swift current.

By the third year of "pearling" some 150 miles of the river was being worked. It was in 1899 that Dr. Myers shipped the first car of shells to Lincoln, Nebraska, for button-making after learning the shells were valuable for this purpose. Up until this time the shells were thrown away after being opened searching for pearls. "Men from the Northern States began pouring in, teaching the people to save the shells and how to boil them (to open them). Some were only. shell buyers while hundreds were what they called 'shellers'. It was these men that brought more sophisticated equipment for digging shells and then the work could be carried on the year round.

Dr. Myers reported, ''as determined by the home banks and express $1,271,000 was paid out for pearling in seven years. "The run down was as follows: paid out for pearls in 1897, $11,000; 1898, $55,000' 1899, $110,000; 1900, $200,000; 1901, $310,000; 1902, $370,000; 1903, $215,000 for pearls and shells.

One of the most intriguing of the pearl stories took place in the spring of 1902. It was then that news reached the streets of Black Rock that a super-pearl had been found on the Julia Dean Bar, located midway between Black Rock and Pocahontas. This bar reached entirely across the river where shellers could wade. The pearl was taken from a large rough shell mussel, known to river people as a mucket, by a man named McCaleb, hence, following the order of the river, it was known as the McCaleb pearl. Pearls at this time were bringing a good price and men knowledgeable and those not so knowledgeable became pearl buyers. w. 0. Bird, a former druggist and jeweler in Black Rock, was such a buyer. He had an office on Main Street and was one of the more knowledgeable buyers. A dealer by the name of Conner told Mr. Bird about the McCaleb pearl. He being one of the first dealers to see the pearl as he was near the bar when it was found. He told Mr. Bird of its size and perfect ball shape. Since Mr. Bird wanted the pearl, he and Conner reasoned together and it was decided that Conner would try to make the buy for $1,000 in cash, that is, if he could beat a Memphis buyer to the bar. Mr. Conner had in his dealings with the river people made a study of their nature and reactions, particularly in business matters, and believed that with the cash approach, ten one hundred dollar bills spread out fan shape before McCaleb, he could get the pearl.

Conner stood in line with waiting buyers. There were five ahead of him including the one in the shack but no sign of the Memphis buyer. From the other buyers, he learned the price was upto $820. The buyer emerged from the shack, he had made a few dollars raise and been refused. The next two buyers in line stepped aside, saying they could do no better . There were only two ahead of Conner now with Holt, a buyer from Newport, waiting after him. The two in front of Conner were worried and ill-at-ease. One at a time they entered and returned to leave without a word.

As Conner entered the shack a motor boat landed and a stranger came toward the camp. Conner marked him as the buyer from Memphis. Inside the shanty, McCaleb, a bronzed knight of the river, sat by a rough board table. On the table rested a cigar box filled with dirty cotton, in the center lay a handful of clean, white cotton and on this rested the pearl. The box cover was closed as Conner had examined the pearl -this being his third trip to the camp. A revolver lay on the table while two shotguns were leaning against the wall. An old man, a relative of McCaleb, stood by the table. Conner entered, spoke to McCaleb and his male companion then advanced to the table. In a low tone of voice he talked to the pearler a few minutes then from his pocket he took ten crisp one hundred dollar bills and laid them fan-shape on the table. McCaleb called the older man -even the woman came to the rim of light and waited. They talked a few minutes -a hushed uncertain silence followed -McCaleb nodded,

they raised the box lid, Conner removed the pearl, placing it in a chamois skin bag and put it in the pocket where the thousand dollars had been. He made one request that McCaleb close the box and not let it be known the pearl had been sold until he was well on his return trip down the river .Mr. Bird took the pearl to St. Louis for appraisal then on to New York where he was advised to join a group of dealers in precious stones on a trip to Paris, France, where the pearl was sold and the people at home were told that it became a part of the royal collection.

What the McCaleb pearl sold for was never known by the people of Black Rock. Mr. Bird returned home, sold all his property and holdings and moved back to his former home in Iowa. He made several trips back to Black Rock to greet old friends and stand in reverie on the bank of the river that mothered the beautiful pearl.

Other valuable pearls have been found in Black River but none of the stories so interesting and spell-binding as that just retold. It is a known fact that a few of the finer pearls from Black River became apart of the crown jewels of royalty in Asia and Europe.

This has all been an introduction to the all so important industry to those in and around Black Rock for so many years, button-cutting. As a result of the interest in pearling and learning the value of shells and for what they were used a button company was formed in February 1900 by Dr. Myers, Dr. N. R. Townsend, and H. W. Townsend. A small plant was built at Black Rock. The little factory began turning out blanks (rough buttons) cut from shells the following May. This was the first button factory in the south according to Dr. Myers. However, after operating only for a short time, the cutters went on strike and the factory closed. The factory was bought and enlarged by a Davenport, Ohio, pearl button company. Button Cutting Becomes A Black Rock Industry

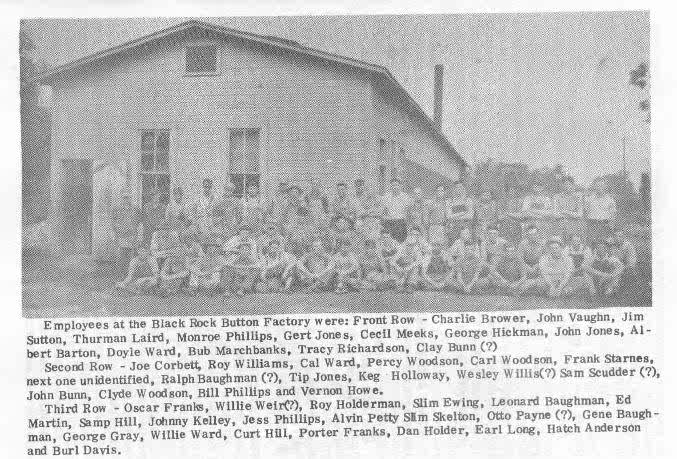

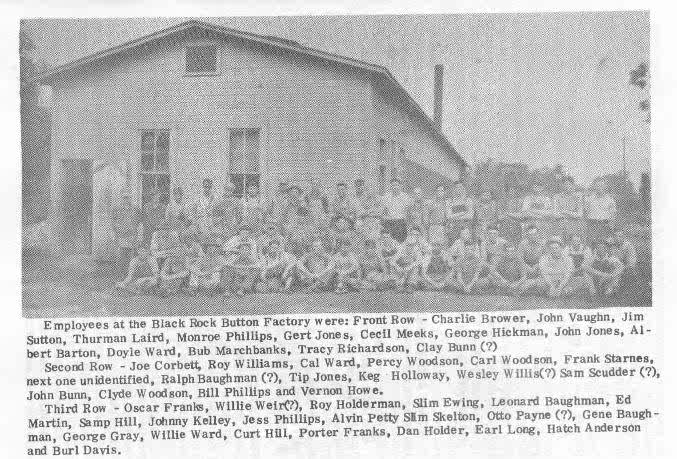

A New York based button company, Chalmers, carried on the button-cutting operation on the river bank at Black Rock for many years in two different locations. First close to the river which flooded the factory sometimes, and later, somewhat farther from the river's edge and on higher ground. It was here that the tanks and crumbling foundation remained until a few years ago. The factory employed 64 cutters, 5 day men (they graded shells and filled the tanks), I straw-boss, I office girl, and I supervisor when in peak production. Their week often consisted of only 3 days work but there were times when they worked five days a week. There were often many shut downs during a year's time. An example of the shut downs and restarting of the factory is the year 1933. The factory opened January 9, shut down Feburary 2, started March 8, shut down March 30, started May 17, (worked four days a week, 9 hours a day), June 12 shop started running 50 hours a week, August 7 shop started 8 hours a day, five days a week, shut down September 1, started September 2 (2 days), shut down September 20 and didn't start again until January 2, 1934. This tells us the button-cutters life was very insecure at times.

Many of the shells for button-cutting came from the Black and White River in Arkansas but in later years most of them were shipped in by railroad cars from the Tennessee and Wabash Rivers. The names of the shells used for button-cutting are fascinating. The shape and texture of the shell helped determine its name. Some of the shells used at the Black Rock factory were: muckets, niggerheads (made most expensive buttons), sandshells, (used more for pearl handled knives, etc.), grandma, washboard, cucumber, three ridges, pigtoe (only one not found in Black River came from the Tennessee), Maple leaf, and the creeper which was thin as paper .

The little better than average cutter in 1933, the year used as an example before, might make as little as $1.56 to as much as $21.45 per week depending on how many days and on which line the cutter worked. The wage a cutter would make in a year's time with the shut downs, etc. would be about $240.59. These figures are based on a journal my dad kept for the year 1933. He was considered to be just a little above average cutter.

The cutting of buttons is an interesting procedure. After the sheller dug the shells and the shells were boiled out, they were transported to the factory either by rail or sacked and brought by wagon to the local factory. At the factory the shells were loaded into huge storage bins, which could hold 500 tons, waiting their turn to be dumped into one of a dozen 1,000 gallon tanks where they would soak and soften for two weeks in steam heated water .

After softening the shells were moved by wheelbarrow to a chute leading into the factory grading room, where they were separated according to the size button they would best produce.

Inside the factory workroom, cutters at machines cut buttons in all sizes. The number of the line indicated the size of the button being cut with line 14 being the smallest going up by two's to line 36 which was the largest and about the size of a quarter. The machines had small saws that looked like. miniature stovepipes with teeth filed in one end. The shell edge gripped by tongs and pushed against the rotating saw by a wooden peg in a mechanically operated pusher. The result was a pellet-like portion of the shell that could be polished and drilled to become a button. Only one button could be cut at a time. The pellets, already called buttons, fell into buckets below the machine. Once a week, usually on Saturday morning, each cutter would take his weeks work to the grading room. The inspector would then take a quarter of a pound of the pellets and examine them, counting the good ones and discarding those not correct in size. He would determine the percent of acceptable buttons upon the examination of this quarter of a pound. If the cutter's "test" was 308, he had 45 pounds, and he was cutting line 18 regulars his take home pay would be about $5.43. The cutter was paid 5 to 16 1/2 cents for each 168 (gross) acceptable buttons he cut. The buttons were washed, put in a power shaker to discard all but the correct size buttons - then they were put into a drum with ridges on its interior surfaces where the buttons were polished. After polishing, the smooth buttons were sent to a factory in Amsterdam, New York, which drilled the eyes and placed the buttons on cards.

The Button Factory was a major industry for Black Rock from 1900 to the 1950's. It reached its peak in the mid 40's and finally had to bow out gracefully and give way to the mass produced synthetic button, which could be turned out more quickly and cheaply.

There are all kinds of nostalgic memories connected with button-cutting by those of us reared at Black Rock where our fathers made their living at this tedious work. Some of these memories are happy ones; others, when the factory shut down, are not so pleasant to recall, but the former far outweigh the latter.

If you are interested in viewing a button cutter's tools, there are some on display at the Old Powhatan Courthouse Historical Library and Museum.

This article could not have been written without the invaluable help of Garnet Vance who furnished all the newspaper clippings from which I gleaned my data, also I want to thank my dad for letting me use his daily journal recording all his years of cutting buttons and for sharing his memories which brought life to this article.

Glynda Stewart, Powhatan, Arkansas